by Ceasar McDowell

Keynote at Grantmakers for Effective Organizations Conference on June 11, 2015.

Direct Experience

This story begins for me when I was in Central America and had terrible fall and I could hardly walk. I was medi-vaced back to the US where doctors gave me x-rays, bone scans, and cat scans, but they were unable to discover what was wrong. Everything changed for me when I visited a holistic doctor. She laid me on the table and proceeded to touch my body all over.

What I realized at that point was that up until then, doctors were trying to understand me by looking mainly at representations of my body. It was not until someone engaged my body physically that the missing information was included that led to a pathway to health. This experience of representative data failing and direct experience finding a solution to a problem left a lasting impression on me—literally. As you can see, I am moving and healthy now. It helped me understand that what we know how to measure is not all we need to know in order to understand.

Thank you for the opportunity to talk with and have a conversation with you about community knowledge and voice. One thing I have learned is that this topic is not just a concern for grant makers. It is also the core issue for building a just and inclusive democracy.

To illustrate this and open a dialogue on the implications for grant making, I am going to tell you about an innovative approach to bring community knowledge and voice to a central public policy issue going on right now here in Boston.

All In

I have spent my life practicing and innovating what it takes to bring community knowledge to how we build equitable and just societies; or, as I like to say, for us all to be all in. All in framing issues. All in providing the information and knowledge needed to understand the issues that affect us. All in making decisions that impact us all. All in, especially those who are most often always left out.

In this and many other countries, we do not have the infrastructure nor process in place that will allow us to be all in, and to bring the full force of what we know to inform our understanding of the world.

And so we are left wondering—How can we build the will and develop the skill of the diverse public to collectively create a just society? How can people live in peace on a healthy planet, balancing their individual interests and complex differences? I call this quest to create a new infrastructure and process to bring us all in BIG DEMOCRACY.

Right now, in Boston, we are using transportation planning to demonstrate that Big Democracy is possible. And we can do this because it’s a new day in Boston with a new Mayor, Marty Walsh, who has a desire to hear more voices than ever before. Go Boston 2030 is a project of the Mayor’s Office, the Boston Transportation Department, and the Barr Foundation to develop a vision for Boston’s transportation future that is defined by the diverse Boston public.

There are four components to this effort:

- Creating a new context for public participation

- Using questions to engage the public

- Making meaning of public knowledge

- Creating a shared vision

Present Day Dance Theater performs outside the Go Boston 2030 Visioning Lab on May 9, 2015. Photo by Rafael Feliciano Cumbas.

Creating a New Context

For it to truly be a new day in Boston, we had to let the public know we were serious about letting them frame the transportation vision for Boston. We used our Question Campaign technique to get people who live, work, and visit Boston to donate their answer to the following question—”What’s your question about getting around Boston in the future?” We started with a blank canvas and asked the public to fill it in from its own experience.

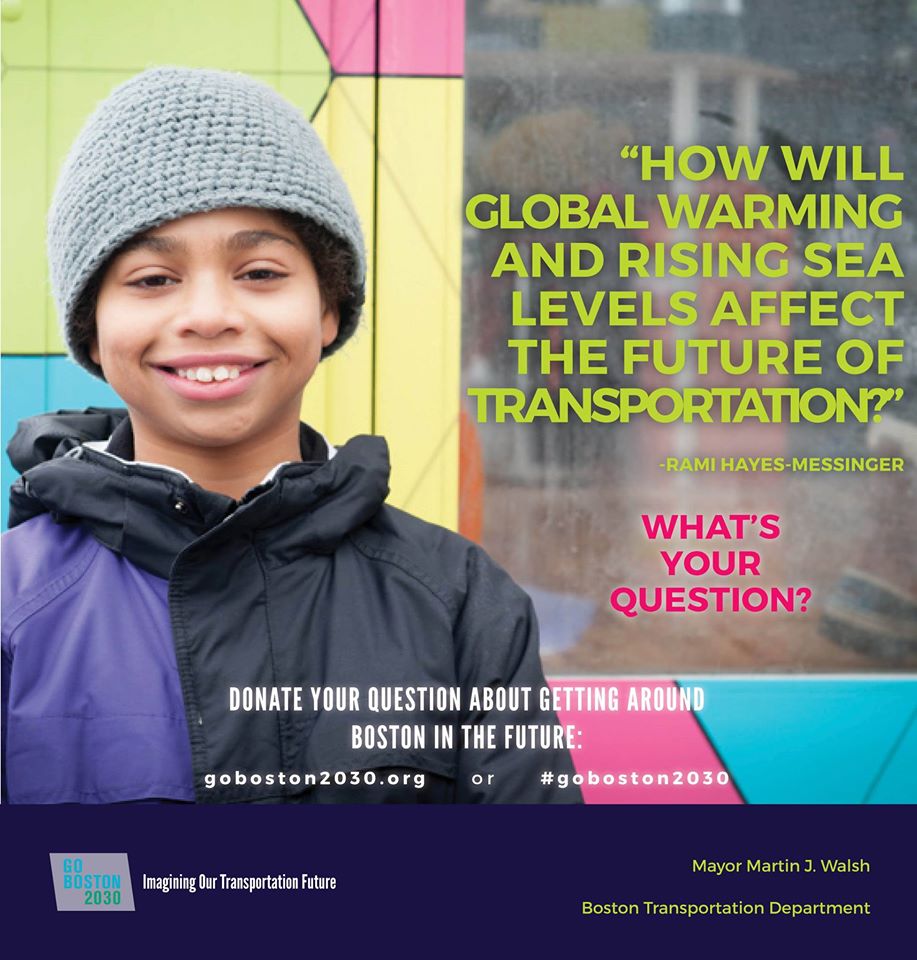

To let the public know the city was serious about hearing from everyone, we created an ad campaign designed to let the public know they were being invited into something different. If this was January, you would have already encountered ads, as they were all over the public transportation, digital billboards, even the trash cans in the city had ads.

The ads were designed to be provocative and to get people thinking about what’s possible beyond their current reality. The ads were also designed to elicit an affective response, to touch people, because we believe that to engage people, we need to engage both their hearts and minds. The ads are also designed to let them know what they needed to do to participate; and all of this because we want to tap into the creative energy and deep knowledge of the public.

What we understand about democracy is that most people have opted out. They believe it is impossible for the demographically complex and diverse public of this country to work together. The counter intuitive action is that, to bring people together, you first create the opportunity for each person to speak for themselves, and, over time, with each other.

Using Questions To Engage The Public

We put our ads throughout the city to demonstrate that anyone can have a question even if they don’t see themselves as an expert in transportation planning. All anyone had to do to participate was donate a question. We use the word donate purposefully to let people know that we recognize their question has value.

To engage people in the process of democracy, you have to lower the barrier to participation. And what we have found is that asking people what their question is about something allows anyone, regardless of age and language, to participate. Even the six-year-old boy who asked the question, “Will dinosaurs be a source of transportation in the future?”

Listening to people’s questions is a way to understand what the breadth of the issue is, what people’s diverse experiences are, and what they most value. Because we believe it is critical for people to see themselves and their reality in the ads, we used our digital channels to reflect back to the public images of people with their questions. We do this to present a counter to the general narrative that is out there that the public is not smart.

In one ad, Rami an 11 year old African-American boy is pictured with the words from his question. “How will global warming and rising sea levels affect the future of transportation?” Knowing that this is the kind of question that he has, how does this change what you think he needs and what’s important in his life?

Big Democracy requires us to shift our thinking and to realize that people, no matter where they are or what their station in life, actually have valuable knowledge to contribute. We learn to value The Other.

Rami Hayes-Messinger quoted in Dudley Square at the What’s Your Question Truck. Photo by Leise Jones.

We collected over 5,000 questions and touched every neighborhood in Boston. We did this by letting people submit a question in a way that makes sense to them and meeting people where they are.

For example:

- People could submit questions via text, email, handwritten cards, Tweet, Instagram, Facebook, and other ways.

- We designed an interactive glass truck that went to 15 neighborhoods.

- We used digital media to publicize on the city’s social media pages, built a following, and attracted thousands of questions.

- We had over 80 partners from city agencies to grassroots organizations committed to bringing their networks into the campaign.

- We participated in existing events all over the city.

We knew it was working because we’d show up at a non-transportation event in the city and get asked for questions. This is something we were part of starting, but the public owned it.

In democracy, in order to solicit the knowledge that the public has, you have to ask people in the form they’re used to having conversations in, and you have to show up where they are. The opportunities for participation have to exist within the normal flow of ones daily life. This doesn’t necessarily mean you, but you have to create the opportunity for the request to show up.

Videos shot and edited by Oluwaseun Ajewole.

Making Meaning of Public Knowledge

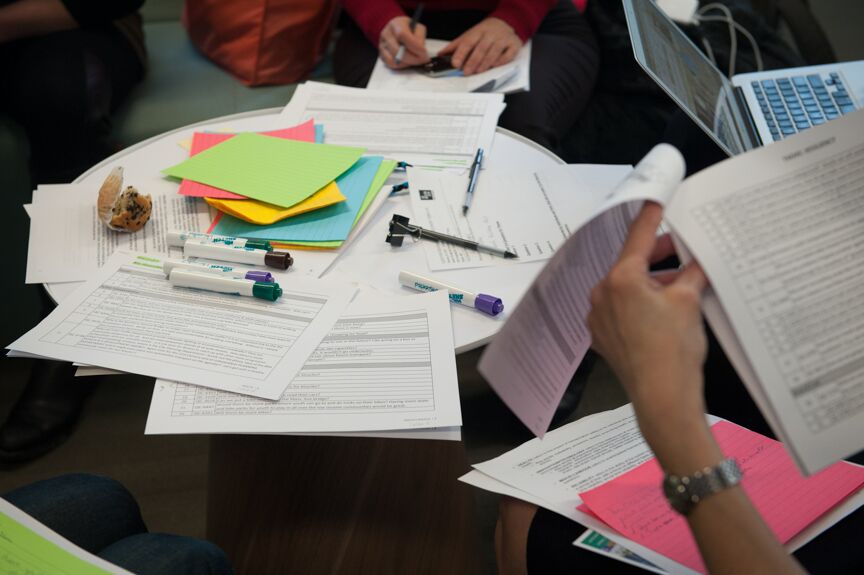

As the questions came in, they were organized by emerging themes and zip code, and made available for viewing on the website. But how do you move from 5,000 questions to something people can anchor around and build a vision? The Question Review Session was a half-day convening of city officials and community leaders who reviewed all of the questions and worked together to understand and articulate what the public was saying. Participants identified sets of questions that best represented what was most recurrent, provocative, and visionary amongst everything people had said.

What is important to note here is that the primary responsibility we ask is that of discernment. They had a responsibility to weigh each question the same and try to discern the shared meaning emerging from what the public had to offer—and they took it seriously. What they produced was later verified by the public at the Visioning Lab. The public will work hard to support open and inclusive democratic processes, and if you are transparent, the public will actually trust the process.

Democracy requires that we have open, transparent processes so when community knowledge is refined by others, it is not set in stone. Once refined, it requires a process of affirmation from the public again.

Every question was read at The Go Boston 2030 Question Review Session on February 24, 2015. Photo by Leise Jones.

Creating a Shared Vision

The Visioning Lab was a place for people to share their vision of our transportation future. It was designed to test the resonance of the themes, questions, and vision ideas that emerged from the Question Campaign and Question Review Session. People were invited to answer some of the key questions and to articulate how they imagine seeing each vision idea come to life.

The 2-day event was highly interactive. Large, multi-lingual walls were created for each theme that emerged from the Question Campaign. Participants could offer their own vision through words or images, build on other people’s ideas, and indicate what content most resonated with them. The walls also included images that were submitted from the public online via the website. In the same area were info graphics drawn from multiple data sets showing how people get around Boston. This input became the basis for informing the goals and targets of the transportation plan.

Mayor Walsh opens Go Boston 2030 Visioning Lab at China Trade Center on May 8, 2015. Photo by Leise Jones.

The vision lab reveals an important point of Big Democracy. If you were to look at one of the theme panels you would notice that at the top is the theme, below are the framing questions, then people’s ideas represented in different forms, and, at the very bottom, a place to vote. In Big Democracy, voting is an artifact of democracy because the real work of democracy is creating the opportunities for people to lift up their knowledge and make meaning together. This is the opposite of where we currently place our emphasis in supporting democracy. As the next presidential election comes into focus, funders will begin to prioritize much needed Get Out the Vote campaigns. However, if we understood voting as an artifact of democracy, we would also be supporting efforts to have the public frame and discuss the key issues that inform the presidential election.

Right now all the information from the Visioning Lab is being pulled together to set the goals and targets for Boston’s transportation plan, and those votes that people cast have actually set the priorities of the themes. They are informed decisions. In January 2016, the city will start designing projects to meet these goals and targets, and open a new process to engage the public in that phase of the work. Interaction Institute for Social Change is in the process of continuing the public engagement in that effort, continuing to help build the public’s muscle for democracy. The questions that have been collected have been organized and coded in such a way that, as projects are identified, we can call up the questions connected to that project and use them to define effective solutions.

Interventions in Democracy

I started out this talk by lifting up the distinction between Big Data and community knowledge. We live in an information economy and data will always be an important part of what we need to consider in making decisions. However, if we want to strengthen democracy, data alone is not sufficient. We need more robust interventions in democracy.

Like the holistic doctor who figured out what was wrong with my back by touching it, we need to reach out and understand communities. We need interventions in democracy. That holistic doctor has a deep knowledge system in place that allows her to do that. We need to work to develop a knowledge system for working with the public.

Just as we are creating the infrastructure to both lift up a holistic approach to health and integrate it with traditional medicine, we need to do the same thing with building democracy. We need to intentionally build an infrastructure that is going to support community knowledge to sit with data. Holistic medicine is growing. It’s widening. It’s deepening. It’s integrating with and becoming part of how we think of traditional medicine. Just as we’re getting more conscious about holistic health, we’re also valuing and getting better at traditional forms of health and data.

So what does this tell us? It tells us that the public is hungry for Big Democracy, but for it to work, every institution that touches the public must take on the responsibility of building the democratic muscle of the public. Every institution that touches the public has the possibility of building the democratic muscle of the public.

To do so we need to:

- Design processes that allow the public to bring their knowledge into the conversation.

- Create imaginative ways to let people know they are being invited into something different.

- Invite conversations that honor what people already know.

- Refine what comes out of public process openly, checked by the public.

- Structure accountability methods into the implementation phase.

Much of what I have presented here is about what structural things we need to create in support of democracy, but the path is not all structural. There is a simple step that each of use can take every day to make sure that, through our actions, we are creating a world in which everyone is in. Just as we know that to undo structural racism we have to attend to the micro-aggressions that happen every day. In building a democracy where everyone is in, we have to create micro-inclusions—daily actions that signal to a person that they are included. We have to build Big Democracy and demonstrate that it is possible for the public to be all in.

About Ceasar McDowell

When asked what his work is about Ceasar always says, “Voice.” He has a deep and abiding passion for figuring out how people who are systematically marginalized by society have the opportunity to voice their lived experiences to the world. Ceasar believes that until people are able to lift up those experiences, they will be unable to participate as full members of society. Over the past few decades, Ceasar has been involved in many activities to bring this belief to life. As founder of MIT’s Co-Lab(previously named Center for Reflective Community Practice), Ceasar works to develop the critical moments reflection method to help communities build knowledge from their practice or, as he likes to say, “to know what they know.” Through his work at the global civic engagement organization, Engage The Power, he developed The Question Campaign as a method for building democratic communities from the ground up. At MIT, Ceasar teaches on civic and community engagement and the use of social media to enhance both. In addition, he is working to create a model of equitable partnership between universities and communities and to support communities to build their own knowledge base. Ceasar brings his deep commitment to the work of building beloved, just and equitable communities that are able to – as his friend Carl Moore says – ”struggle with the traditions that bind them and the interests that separate them so they can build a future that is an improvement on the past.”