The System Is Us

September 22, 2011 3 Comments“If you don’t see your role in contributing to the problem, then you can’t be part of the solution.”

-David Stroh

David M. Nee, Executive Director, William Caspar Graustein Memorial Fund from Graustein Memorial Fund on Vimeo.

Yesterday I gave a general update on the proceedings of the Right from the Start early childhood development system change effort in Connecticut. Today I want to lift up some of the insights and wisdom that have been unearthed by the System Analysis phase. Key to this work has been the engagement of two experts in the realm of systems thinking – David Stroh of Bridgeway Partners and Keith Lawrence of the Aspen Institute’s Roundtable for Community Change.

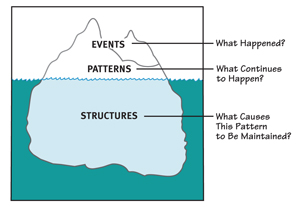

David brings particular skill and experience in teaching about and mapping systemic dynamics as they play out at different levels. In June, he gave a wonderful overview of systems thinking to the System Design Team, which included an introduction to the iceberg diagram (see below) that helps people get from more superficial and tactical questions to deeper systemic points of leverage, including awareness of one’s own unwitting contribution to dynamics that yield outcomes that are undesirable or in some sense not optimal. Part of the shift we experienced over the course of these conversations was the understanding that “the system” is not out there, but as Yaneer Bar-Yam says, is “the way we work together.” As we engaged participants in various exercises (including Rich Pictures, and working groups organized around focusing questions) to get a better picture of what exists as an early childhood system in Connecticut, the attempt was also to draw attention to the foundational structures (policies, pressures, power dynamics, perceptions, and purposes) that if addressed might help shift the overall system toward more desirable outcomes.

Keith Lawrence joined us in June as well with an important presentation on structural analysis and institutional racism. His contributions were designed to help us go beyond “the data” and considerations of overt and legally sanctioned, as well as individual forms, of racial discrimination to the “racialized patterns [that] permeate the political, economic, and socio-cultural structures . . . in ways that generate differences in well-being between people of color and whites.” Referencing the Aspen Institute’s report Structural Racism & Community Building, Keith helped would-be system changers understand the complexity of structural racism as “the system in which public policies, institutional practices, cultural representations, and other norms work in various, often reinforcing ways to perpetuate racial group inequity in every key opportunity area, from health, to education, to employment, to income and wealth.”

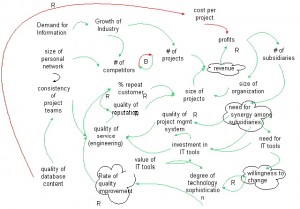

With this foundation, four working groups engaged different curiosities about the early childhood system in Connecticut (how it is and why this is so) by looking at it from the angles of government mis-alignment, disparities in outcomes and quality of services, as well as disparities and mis-alignment of formal and informal infrastructure to support families and children at the local level. All of this culminated in the production of a system map (see generic example below) by David Stroh, outlining key dynamics in the early childhood system, including links and feedback loops.

The most recent discussions Melinda and I have had with the System Design Team in the System Analysis phase have focused on the case for NOT changing the system/ourselves and the case for changing it/us. This has proved to be very valuable and powerful, as the point was made by David Stroh that all systems are set up perfectly to yield the results they are producing. Someone or something always benefits, at least in the short-term. In order to build momentum for systemic change, the sum of the benefits of change and the cost of not changing must be stronger than the sum of the cost of the status quo and the cost of changing.

The most recent discussions Melinda and I have had with the System Design Team in the System Analysis phase have focused on the case for NOT changing the system/ourselves and the case for changing it/us. This has proved to be very valuable and powerful, as the point was made by David Stroh that all systems are set up perfectly to yield the results they are producing. Someone or something always benefits, at least in the short-term. In order to build momentum for systemic change, the sum of the benefits of change and the cost of not changing must be stronger than the sum of the cost of the status quo and the cost of changing.

Having begun to flesh out the case for moving forward, the System Design Team has also surfaced some possible leverage points, or areas in the system’s current dynamics and relationships where intervention might help shift to different and desired outcomes. These include: building stronger relationships and a “village culture” in and between communities, better connecting and coordinating local and state as well as formal and informal supports, making a stronger long-term business/economic case for investing in the earliest years of a child’s life, and focusing more on “the preparation gap” not just the “achievement gap.”

From here we take the map and the highlights of our conversations to communities across the state to hear what resonates about the current state of affairs, the case for change and possible leverage points, and to engage citizens in a conversation around the following questions: “What would a high quality and sustainable early childhood system that is accessible and effective for all children and families look like? How would you be experiencing this system from where you sit, given your role(s) in the system (child, parent, provider, advocate, legislator, etc.)? What would be different and better about this, for you and others in this state? And what foundational beliefs and values would guide this system?

From here we take the map and the highlights of our conversations to communities across the state to hear what resonates about the current state of affairs, the case for change and possible leverage points, and to engage citizens in a conversation around the following questions: “What would a high quality and sustainable early childhood system that is accessible and effective for all children and families look like? How would you be experiencing this system from where you sit, given your role(s) in the system (child, parent, provider, advocate, legislator, etc.)? What would be different and better about this, for you and others in this state? And what foundational beliefs and values would guide this system?

3 Comments

Thanks for documenting the work in this way, Curtis!

Thanks for helping me to do the work, Buddy!