The fastest way to kill collaboration? Obscure decision making.

Folks who know me as a facilitator know that one of my first and favorite questions in planning a meeting is “who’s deciding?” It’s a question that can be counter-cultural for groups that are unaccustomed to clearly defining the decision-making process. And yet, leaving the question unanswered or unclear is one of the fastest ways I have seen to erode trust and to drive people away from working together.

Tips for doing better

Answering a few simple questions can help to avoid a great deal of frustration and prevent the fracturing of collaborative work:

WHAT decision is being made? What information will we need to make the decision? What criteria will guide the decision?

WHY is this the decision we’re making? Is there something else that we need to address first?

WHO is the final decision maker? Is it the group that’s meeting now or is it actually some other group or individual?

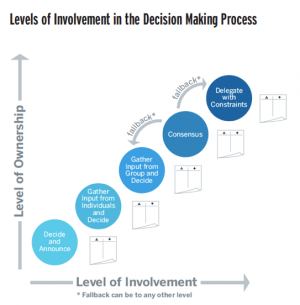

HOW will the final decision be made? If the group is making the final decision together, do they have an understanding of what consensus is and how to reach it? What will they do if they can’t reach a consensus? If an individual is making the final decision, will they gather input from others or proceed alone? How will they share the factors that will be considered as the decision is made? How will people be informed about the final decision? (Check out our Levels of Involvement in Decision Making framework for many more details about options for how to involve people in decision making.) What constraints will shape the decision-making process (e.g., time available, resources needed, etc.)?

Using the Questions in Sticky Situations

Do any of these situations, which we’ve seen repeatedly in our work, sound familiar to you? Here are some ideas about how applying our tips could have helped.

- A team receives a task with minimal guidance about constraints, other than when the project is due. They complete their task and are told, “No, we don’t have time or money to do all of that.” or “That’s not actually what we thought you’d do with the task.” The team is asked to go back to the drawing board but many members feel disrespected and frustrated, and are reluctant to continue working on the project.

The leader who set the team up with the project could have named specific time and resource constraints to help both the leader and the team set clear expectations, and could have indicated what would happen next if the group couldn’t make its decisions within those constraints.

- A coalition is meeting to decide on its goals for the year. A few priorities rise to the top, but there is no moment when the group clearly affirms the choices. Everyone goes away feeling good, but thinking differently about what was actually decided. A few days later, members read the meeting notes, which sound to some participants like they were from an entirely different meeting. Frustration ensues as individuals jockey to get the items they thought were agreed upon onto the final list of goals.

The meeting facilitator could have explicitly checked for consensus as priorities began to emerge, and clearly identified where there was/was not agreement. The note taker could have recorded on chart paper or used a computer and projector (in an in-person meeting) or screen sharing or a shared online document (in an online meeting) so that everyone could see what was happening with the information in real time.

- A team receives a meeting agenda saying that the outcome of the meeting is an agreement on a solution to a pressing organizational problem. During the meeting, people spend all of the time exploring the problem. Some people are frustrated that they didn’t even begin to move towards a solution. Others are frustrated with the stated meeting outcome, since there hadn’t been any problem analysis. The meeting ends without a clear sense of what to do next and what to say to those who are waiting for the solution.

Typically, if a group is deciding on solutions, they first need to understand the problem they are trying to solve so they can identify solutions that effectively address root causes. The facilitator and meeting planners could have designed pre-meeting work or discussions to build understanding of the problem before getting into solutions. Or, they could have shifted the timeline so the group could explore problems during this meeting and solutions later.

- People leave a staff meeting thinking they have reached agreement on organizational priorities. A few days later, the CEO announces priorities, which are slightly different, thanking the group for the way the meeting helped her to make her final decision on priorities. Staff members are confused and frustrated because they thought they were all making the decision together. Some team members begin to wonder if they can trust the CEO.

The leader could have first asked herself whether this is a decision the team should actually make together. If the situation really did call for her to make the final decision after consulting with the team, she could have started and closed the discussion by clearly stating why she is the final decision maker and how this discussion gives the team a chance to inform her final decision.

- A colleague sends you an email, assigning you a task that you didn’t know about and asking you to do it in a way that doesn’t make sense to you. They don’t invite any questions and do not appear willing to discuss your ideas about how to get the job done. You wrestle with how much energy you want to put into asking questions and whether you have the energy to deal with a potential conflict if you just do the task in a way that makes most sense to you.

The colleague could have explained who decided that the task needed to be done in this particular way and why, spelling out important factors that led to this decision. They could have asked for your questions, concerns, or ideas about how to proceed. And they could have explained any degrees of flexibility around how the task was to be accomplished.

While clarity about decision making isn’t magic, it will make many collaborative ventures much smoother. It will grow the precious resource of trust, without which your efforts to work together are destined to fall short. It will also give you new ways to explore and expand power, which is so often experienced through the act of decision making. Questions about who decides on things like priorities and strategy; the allocation of time, money, and other resources; involvement in designing and implementing activities; and who decides who gets a seat at the decision-making table are fundamentally questions about power. Clarity around decision making will create space to address power dynamics more directly and grow more shared power to accomplish together things that you could never accomplish on your own.

Let us know how these tips are helping your efforts to collaborate for social justice and racial equity.For more on power and power dynamics, check out our series Bringing Facilitative Leadership for Social Change to Your Virtual Work, which includes sessions on Managing Power Dynamics in Virtual Meetings and Collaborative Decision Making and Shared Leadership.

Leave a comment