Cultivating Connectivity: Understand the Soil Before You Till

April 19, 2017 Leave a comment

In sustainable agriculture you hear talk about no and low-till farming. These are approaches that emphasize minimal disturbance of soils to preserve their structural integrity and also to keep carbon in the ground. No-till increases organic matter, water retention and the cycling of nutrients in the ground. As a result it can reduce or eliminate soil erosion, boost fertility and make soils more resilient to various kinds of disruptions. This flies in the face of mainstream approaches that recommend ongoing and significant intervention, “fluffing” soil and digging down to considerable depths to get rid of weeds and aerate the ground. What actually happens can be quite destructive to the long-term productive and regenerative capacity of the soil.

“When we harvest, weed, rake or trim gardens and landscapes, we remove the organic material that feeds the soil.”

Elizabeth Murphy, soil scientist

I like this as a metaphor for what can happen when there is failure to see and respect the networked structures that already exist in communities, organizations and other living systems.

I was recently told a seemingly archetypal story about a large funder that entered a community with bluster, pouring in vast amounts of money and showing little interest in existing structures, innovations and initiatives. This churning and turning of the community ground ended up being extremely disruptive, resulting in the release of anger and angst towards the funder, pitting community members against one another in competition for resources and leaching valuable assets of time and trust. Not only was the venture a failure, you could say that it left the community poorer than before!

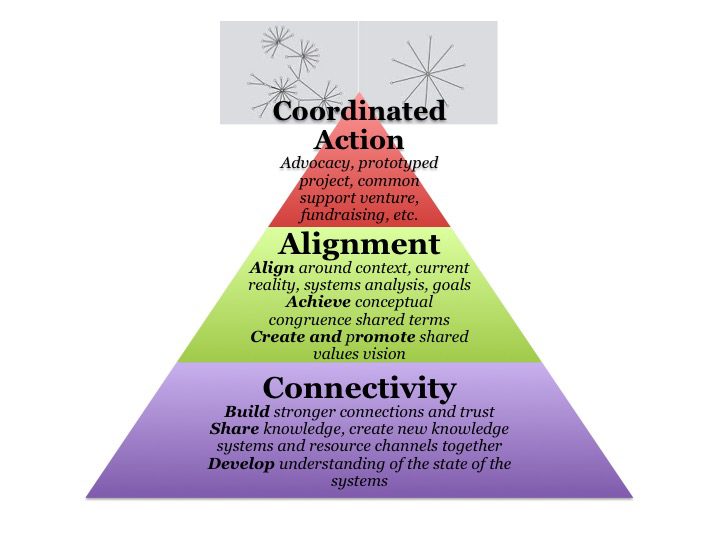

Attending to and investing in connectivity is not always the sexiest thing for funders and other would be supporters of social change efforts. It does not often address the sense of urgency, call to action, and drive for “proof of impact.” That said, not stopping to understand and appreciate a community’s dynamic organic matter – relationships, network patterns and resource flows (often a source of great strength in resilient communities facing daunting circumstances) – can lead to irresponsible and damaging interventions.

Attending to and investing in connectivity is not always the sexiest thing for funders and other would be supporters of social change efforts. It does not often address the sense of urgency, call to action, and drive for “proof of impact.” That said, not stopping to understand and appreciate a community’s dynamic organic matter – relationships, network patterns and resource flows (often a source of great strength in resilient communities facing daunting circumstances) – can lead to irresponsible and damaging interventions.

“I am not who I thought I was. And neither are you. We are all a collection of ecosystems for other creatures. But it’s not just the microbes themselves that add to who we are. They add to our genetic repertoire.”

I am reading a fascinating book by David R. Montgomery and Anne Bikle entitled The Hidden Half of Nature: The Microbial Roots of Life and Health (from which the quote above is taken). In it the authors orient readers to Earth’s smallest, oldest and most resilient creatures, residing in the ground and our bodies, that are critically important to plant and human health. In so doing, they help us to understand a different story about life and liveliness – we constantly benefit from otherwise hidden dynamics and connections. The costs of our ignorance of this reality seem to be rising, whether we are talking about how we treat soils and seas, our bodies, one another (or the perennial “other),

The invitation then is to slow down, take a closer look, observe what is already happening to support resilience, adaptation, innovation and regeneration. The best course of “action” is generally to respect and work with this. As is the case with malnourished soils, there may be a call for greater intervention, and it is important to understand the implications of flooding, artificially fertilizing or busting up the community ground.

In social change work it may be important then, inspired by this season, to think more like gardeners, and to heed the wisdom of the poet, in this case the ever perceptive Marge Piercy:

Connections are made slowly, sometimes they grow underground.

You cannot tell always by looking what is happening.

More than half the tree is spread out in the soil under your feet.

Penetrate quietly as the earthworm that blows no trumpet.

Fight persistently as the creeper that brings down the tree.

Spread like the squash plant that overruns the garden.

Gnaw in the dark and use the sun to make sugar.

Weave real connections, create real nodes, build real houses.

Live a life you can endure: Make love that is loving.

Keep tangling and interweaving and taking more in,

a thicket and bramble wilderness to the outside but to us

interconnected with rabbit runs and burrows and lairs.

Live as if you liked yourself, and it may happen:

reach out, keep reaching out, keep bringing in.

This is how we are going to live for a long time: not always,

for every gardener knows that after the digging, after the planting,

after the long season of tending and growth, the harvest comes.

-From “The Seven of Pentacles”