Letting Go for Life, Liveliness and Possibility, Part 2: Steps and Supports

August 29, 2017 2 Comments“For a seed to achieve its greatest expression, it must come completely undone. The shell cracks, its insides come out, and everything changes. To someone who doesn’t understand growth, it would look like complete destruction.”

–Cynthia Occelli

Photo by lloriquita1, shared under the provision of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0.

In the late spring, we had an unseasonably sticky stretch of days where I live, and after school one day, my wife and I took our girls to a local swim hole to cool down. As we eased into the cold water, one of our seven-year-old twins clutched desperately to my torso, not yet willing to put more than a toe or foot in. As the sun beat down, I began to feel both the weight of her body and the ebb of my patience, and I managed to negotiate her to a standing position in water that came to her waist. She continued to clutch my arm vice-like with both of her hands.

After another few minutes it was definitely time for me to go under water. But Maddie was unwilling to release me. I continued to encourage her to let go first, to get her head and shoulders wet. Initially totally reluctant, she got to a point where she was in just up to her neck but was still anxiously squeezing my hand. We did a bit of a dance for a few minutes where she would get to the end of my finger tips with her right hand, seemingly ready to take the plunge, and then the same part-anticipatory part-terrorized expression came to her face and she was back against me.

I kept coaxing her, and then let her know that whether she let go or not, I was going under, and if she was still holding on to me, that she would be doing the same. “Okay, okay!” she yelled, stamping her feet and once again got to the tips of my fingers while breathing rapidly. And this time … she let go. She pushed off and immersed her entire body in the water. She came up shrieking but with a big smile on her face, a bit shocked but also more at home in the water, moving around quite gracefully, actually. She splashed me and laughed and then I dived in. A few minutes later she was swimming along next to me.

Image by Donnie Ray Jones, shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0.

I share this story because it is one I hold in mind quite often as I think about and do work with myself and others around the crucial process of letting go. As I wrote in a post a few weeks ago, letting go (of certain practices, structures, patterns, beliefs, expectations) is a requirement for development, adaptation and evolution. And this can be the hardest part of change, even as we may know that what currently stands cannot continue and what has served us to a certain point no longer will. But how to let go?

How do we release our hold of the familiar shore even when the other side is not yet in view?

One recommendation in my last post was a thought exercise offered by Nora Bateson, the invitation to take a mental trip through the unraveling and breakdown of a system or situation, going to the other side of what is feared and then asking how we would get along. Traveling back to the present from that point, we can ask what wisdom we might incorporate that breaks our current patterns? How might that help us to loosen our grip and to go more with the flow?

In exploring this question further over the past few weeks, through reading, conversation and reflection, I have surfaced some other supports that can assist with the vital process of letting go and letting come.

“[The person] who is not busy being born is busy dying.”

–Bob Dylan

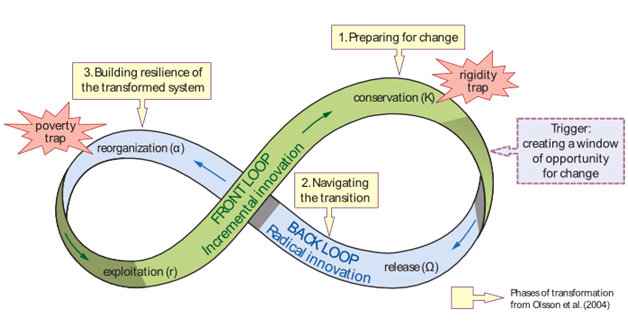

The Adaptive Cycle: To Let Go Is Natural

One great support is the adaptive cycle, a framework that I spoke to in my last post on this topic, which offers a perspective on how living systems evolve over time and go through natural cycles of growth, (relative) dissolution and reorganization. According to this framework, at the peak of a system’s cycle of maturity (see #1 in image above), during which it has conserved resources and established predictable practices and protocols, it threatens to become too rigid and unable to respond to inevitable changes in its environment. The key to avoiding collapse at this point is both a release of energy (#2) and an embrace of more radical (as opposed to superficial) restructuring.

In other words, one way of helping with the release process is to understand that it is quite natural and necessary. Unchanging rigid systems and practices are prone to breakdown and collapse, precisely because they do not respond to changing conditions (think about the proverbial frog in slowly boiling water). As my friend Joel Glanzberg says, living systems become senescent (old, decrepit, weak and prone to the ravages of aging) without disruption to their practiced ways. We can do ourselves a favor, then, by keeping open to change and newness.

Are there ways then to proactively embrace creative disruption that anticipates or encourages more productive and desirable practices?

Photo by Hamed Saber, shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0.

“Observe, observe this river of life flowing through your existence–if you fail to grasp it, it will elude you.”

–Michel de Montaigne

Abundance Thinking: There Is More Than Meets the Eye and Mind

A potentially fertile area in this regard is “abundance thinking,” as discussed by the likes of permaculturist Looby Macnamara. As Macnamara points out in her book 7 Ways to Think Differently, how one approaches a situation matters. Coming to the endeavor of change with a “scarcity mindset” (“there is not enough,” “there was already not enough and now there will be even less,” not trusting others, being overly protective of one’s resources, etc.) will lend itself to rather limited approaches.

Of course, scarcity can be very real, and there are times and situations in which to be careful and protective. Furthermore, the word “abundance” can be used in certain situations in ways that are harmful, especially when there is little demonstrated understanding of existing structural inequities, which can result in “blaming the victim” and preserving privilege for the privileged. That said, “leading with abundance” as a mental exercise can prove useful to exploring the process of letting go and inviting the new. Here are a few thoughts:

- Coming with a sense of gratitude for what one already has, a willingness to share and eagerness to learn what others have to offer, can yield different insights and options. One strategic question is whether a view of or belief in scarcity or deficit is a default approach and reaction, not actually rooted in reality, and whether being intentionally grounded in abundance, gratitude and generosity might reveal greater possibility. There is interesting research in the field of positive psychology that shows how gratitude and being more open in one’s approach can actually create more opportunities through greater and enhanced perspective.

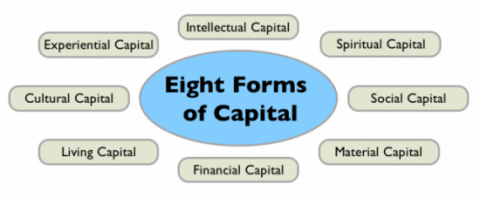

Image from Appleseed Permaculture

- How one defines capital, wealth, and abundance matters. Macnamara highlights the work of fellow permaculturalists Ethan Roland and Gregory Landua to expand how wealth is understood. For example, Roland names eight different forms of capital: intellectual, spiritual, material, cultural, material, social, living, and experiential. Macnamara adds health and well-being capital to these. The point is to see wealth and assets from a more holistic perspective and to help people see their own resource-full-ness in a different light, not simply defined by others or more narrow understandings. Furthermore, looking at capital in a more multi-faceted way can help direct attention not simply to lacks, but “what is already flowing” and how this might be leveraged.

- How one sees and understands “problems” and opportunities matters. One of the most exciting and challenging principles for me in permaculture is the idea that “the solution is the problem.” In other words, every problem (or ending) when viewed in a certain way may have seeds of opportunity or beginning. This is what is behind the idea of re-purposing what is otherwise “waste” as food for another part of the system (compost, recycling, orthogonal thinking). Again, this can be tricky given different systemic perspectives and social inequities. Recasting someone else’s problem as an opportunity is not necessarily the idea, and can certainly become the source of more problems. But working to see what at first blush seems like a challenge or limitation or lack, in broader and more opportunistic terms seems smart and strategic. This is what has led some people, for example, in those areas more impacted by rainfall from climate change to think less in terms of simply mitigating floods to becoming harvesters of water.

Artists certainly know that abundance thinking can help recast “constraints” as catalysts of creativity, which can assist with movement through the adaptive cycle and embrace of novelty.

What might we learn from a closer look at the creative process?

Photo by jar [o], shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0.

“A living body is not a fixed thing but a flowing event, like a flame or a whirlpool.”

– Alan Watts

Strengthening Flexibility: Discovery Through New Perspectives

For the past few months, I’ve been savoring the book The Net and the Butterfly, which is full of examples and suggestions of methods for opening one’s mind to “breakthrough thinking.” The point of the authors, Olivia Fox Cabane and Judah Pollack, is that in order to have insights that lead to new ways of doing and being, we do not have to be gifted inventors or artistic geniuses. What we do need, however, are ways to create space for insights to emerge and to notice them.

The common theme underlying the practices that the authors explore is supporting the neuroplasticity of our brains, their ability to rewire themselves for new thinking. Neuroplasticity happens on its own, to a certain extent, but is reduced by practiced habits and routines. This happens as we age and get too comfortable with the familiar. So in order to encourage an embrace of novelty, here are some suggestions from the book:

- Stop trying to figure it out. Simply grinding on a problem or challenge or sitting in fear and frustration can prevent solutions from showing up. Create space for new insights to emerge by giving your mind a rest – take a shower, take a walk, relax and breathe, or engage in relatively mindless activity (wash dishes, bounce a ball).

- Try on a new perspective. Looking at the world differently can help us to see the world differently and to see possibilities we had not seen from our usual vantage points. Read literature from different and unfamiliar disciplines. Talk to someone who sees the world differently (culturally, politically, professionally). Take a different route to work or for your daily walk. Climb a tree (or go to the top of a tall building) to literally get a different perspective on things.

- Use your opposite hand. Research shows that by using our non-dominant hand to perform daily routines (brushing teeth, brushing hair, drinking from a cup) we can strengthen the plasticity of our minds and open up new pathways.

- Open up to different sounds and tastes. Intentionally seeking out and paying attention to new and unusual sensations can also strengthen our mental flexibility and the possibility of having insights. The key is not simply to listen to different kinds of music or sample new flavors, but to really pay attention to what we notice in doing so.

- Learn from the intelligence and wonder of nature. Much has been written about biomimicry and the wisdom of following the larger living world’s innate capacities of resilience and innovation (evolution). Check out this website for inspired ideas from nature or look at the writings of the likes of Tristan Gooley that can help us read the pattern behaviors of natural systems.

Even when we succeed in pushing away from the shore, get ourselves into the flow and begin to explore new waters, there can be a tempting pull to the familiar.

How can we navigate the fear and anxiety that wants to call us back or pull us under?

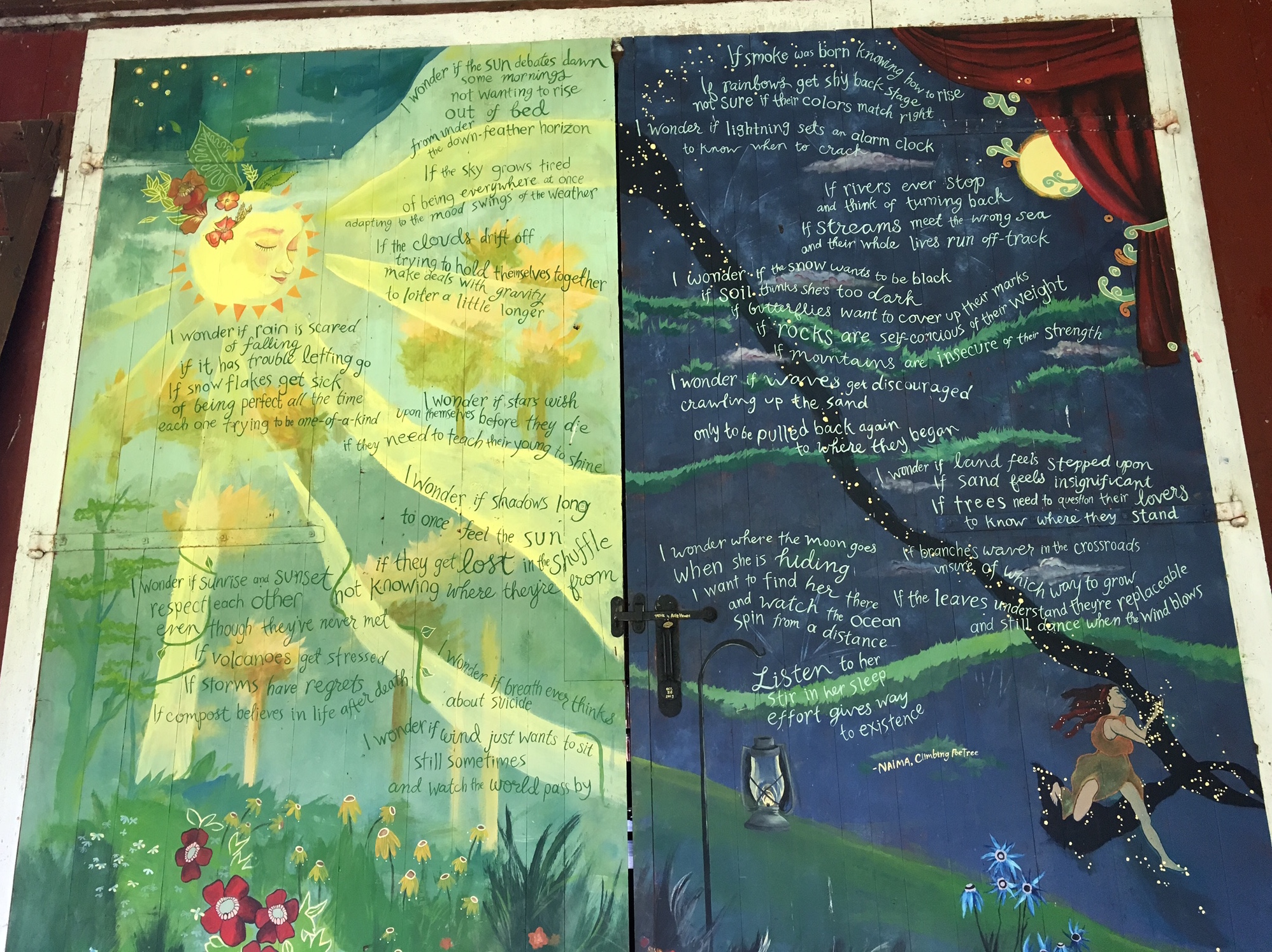

Mural on barn doors at Knoll Farm in Fayston, VT. Text is the full poem “Being Human” by Naima, Climbing PoeTree.

“I wonder if rain is scared

of falling

if it has trouble letting go …I wonder if waves get discouraged

crawling up the sand

only to be pulled back again

to where they began …If branches waver in the crossroads

unsure of which way to grow …”-From “Being Human” by Naima, Climbing PoeTree

Presencing and Focusing: (Re)Grounding in Strengths and Gifts

Over the last several months, I’ve been drawn to different modalities to deal with anxiety stemming from what feels like ongoing volatility and uncertainty in the greater surround. My guides and inspiration have taken many forms, including the writings of Nora Bateson, Gregory Cajete, Movement Strategy Center, Open Democracy, and MAG, among others. I have also been engaged in ongoing work with a focusing practitioner. This study and practice has been invaluable and helped me to stay grounded. Some of the practices that have shown themselves to be helpful in cultivating presence amidst uncertainty include:

- De-coupling from context. I am often outspoken about the value and importance of connecting through network building. But it is also true that disconnecting can be a good move to stay strong. In this case, I am talking about the work of creating a break between our inner lives and the conditions around us. We can very easily take on the stresses of the systems around us. Creating some separation between one’s inner condition and what’s going on around us is key to cultivating resilience.

- Getting out of the head and into the full body. The head only knows part of the story, is often late to the party, and can become a tiresome guest. As a book title puts it, The Body Knows the Score. Focusing and somatic practices can reveal wisdom and feelings in the body that our thinking minds alone would otherwise not readily access. Also moving our bodies (walking, yoga, playing frisbee) can be crucial to breaking cycles of perseveration and worry and inviting new thought patterns.

- Not traveling alone, and choosing partners wisely. Community can be crucial in times of turbulence, and with whom we connect can matter a lot. It has been particularly important for me to be with people who also see themselves on a path of development, are eager learners and good listeners. And generally it is good to be with those who support and challenge us in helpful ways and with whom we feel more alive and authentically ourselves.

- Getting inspiration from those who have gone before. There are so many who have gone before us as agents of change, peace makers and possibility creators. It can be very reassuring to remind ourselves of their struggles and stories. Some of my personal favorites include Howard Thurman, Grace Lee Boggs, Mary Parker Follett and Myles Horton.

“Living is a form of not being sure, not knowing what’s next or how. The moment you know how, you begin to die a little.”

– Agnes de Mille

Photo by Isengardt, shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution License 2.0.

Meeting the World Half-Way: The Power of Mystery

I also personally find considerable wisdom and support in poetry (see Joy Harjo, Li Young-Lee, Elizabeth Alexander, Wendell Berry, Naomi Shihab Nye, William Stafford, Marge Piercy, and Wislawa Szymborska, among others) and make this ending offering of the David Wagoner’s “Lost,” which points to the importance of being humble in navigating change and also attuned to how greater forces can be of support along the way. This makes the process of letting go and exploring that much more inviting to me.

2 Comments

This is so beautiful and insightful Curtis, thank you! I have been in conversation with a network leader who has been discouraged by some funders who have been long involved but still seem to undervalue the contribution and potential of the network she leads even though evidence abounds that the contribution is substantial and the potential is wide open. By the end our conversation we attempted to turn what appears as adversity into a re-frame of “where’s the opportunity”? I couldn’t agree more that we need to live in “Abundance Thinking” and let solutions emerge from there. I’ve shared your post with my network leader colleague in hopes that it will inspire.

Jennie Curtis, Garfield Foundation

Thank you, Jennie. So glad to see your response here, and I appreciate you sharing the post with your colleague. I would be curious to hear what comes of that. Also happy to talk with her directly, about “abundance thinking” and also ways of telling the evolving network story in ways that point to progress that others might value.