Letting Go For Life, Liveliness and Response-ability, Part 1: Why?

July 18, 2017 3 Comments

Photo by Neal Fowler, shared under the provisions of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0.

(I want to give a BIG shout out to Marsha Boyd for helping to inspire this post with her words and spirit. Thank you, Marsha, for your collegiality, mentoring, and leadership by example!)

For the past couple of weeks, I have been savoring a book by Nora Bateson entitled Small Arcs of Larger Circles: Framing Through Other Patterns. Bateson is a filmmaker, writer and activist, and also the daughter of Gregory Bateson, ground-breaking anthropologist, philosopher, systems thinker, cyberneticist and author of Steps to an Ecology of Mind. Small Arcs of Larger Circles is a mind-stretching and heart-opening amalgamation of essays, poetry, personal stories and excerpts of talks. Throughout Bateson offers a ranging exploration of systems theory and complexity thinking with an invitation to embrace a broader epistemological lens (what people think of as sources of legitimate knowledge) including embodied knowing and aesthetic experience.

In an essay entitled “The Fortune Teller,” Bateson explores the human tendency to stave off consciously or unconsciously anticipated disaster and decline by trying to keep things stable or as they have been. Think the most recent financial crisis. A recent article on the site Evonomics entitled “It Takes a Theory to Beat a Theory” reminds us of the story of former Federal Reserve chairman Alan Greenspan, a champion of unfettered capitalism. Greenspan fought against initiatives to rein in derivatives markets even as there were signs of turbulence and calls to make substantial changes. On October 23, 2008, Greenspan admitted he was wrong, making the following statement to the House Committee on Oversight and Government Reform: “Those of us who have looked to the self- interest of lending institutions to protect shareholders’ equity, myself included, are in a state of shocked disbelief.” But what has significantly changed? Or consider a very recent article about local government efforts in Ventura County, California to site a new fossil fuel plant on a beach starting in 2020 that ignore protests from organized low-income residents concerned about air quality and lack of access to the beaches, and environmental organizations pointing out the real danger stemming from underestimations of sea level rise.

Photo by Duncan Hill, shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0

While in some ways understandable (few of us probably like the idea of collapse and chaos), actions taken to preserve a certain kind of order and direction (not to mention power and privilege) can be particularly perverse when they reinforce the very patterns that are leading us down the road to collective ruin. And what more people are beginning to sense is that many social, economic and political patterns that have been established and gotten us to where we are must change for the sake of long-term survival and thriving.

“It takes a great deal of change to keep things the same.”

The phrase above, which appears as a sub-title in Bateson’s essay, caught my attention, even froze me in my reading tracks. She reminds readers that change is a constant in complex living systems, so that stability and sameness over time can take considerable effort to pull off. The effort to keep larger forces from shifting current arrangements is ultimately impossible and in the nearer term it can exact a heavy toll. Bateson notes that trying to keep any part of a complex system still “requires that all the relationships upon which this part is inter-dependent must alter to absorb the shifting.” This can push the entire system toward greater vulnerability. I’m thinking now of a personal example – a recent flirtation I had with burnout this spring, spurred by anxiety about the current political and economic context, which had me pushing myself harder than ever to do work that was already exacting, and in the process putting considerable stress on my family and colleagues.

Letting go is not necessarily giving up; it can be letting come.

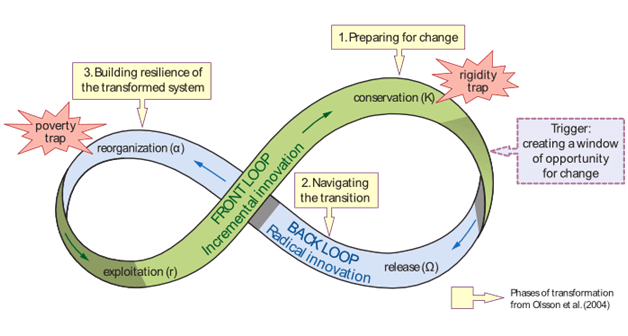

A key framework for my consulting work (and now personal development) is the adaptive cycle. The adaptive cycle offers a perspective on how living systems evolve over time and go through natural cycles of growth, (relative) dissolution and reorganization. According to this framework, at the peak of a system’s cycle of maturity (see #1 in image above), during which it has conserved resources and established predictable patterns and protocols, it threatens to become too rigid and unable to respond to changes in its environment. The key to avoiding collapse at this point is both a release of energy (#2) and an embrace of more radical (as opposed to superficial) innovation. This release may entail letting go of certain goals/expectations, ways of doing things and relationships. This means that some of the energy that is otherwise invested in preserving order and predictability can now be devoted to the generation of new forms and practices (see #3 in image above).

In other words, until there is significant letting go, it is difficult for anything new or renewed to come. To this point, I recently worked with a group of well-meaning academics who all acknowledged that they were being called to do things differently in their work and respective institutions of higher education, to be more relevant to the needs of their increasingly diverse and distressed students and the world that these students must navigate. And yet, by their own admission, they are so overburdened with demands that they can hardly give much more than passing thought or effort to substantive change. By one professor’s assessment, this can amount to irresponsibility of a very dangerous kind.

Photo by Phil Roeder, shared under provisions of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0

Nora Bateson offers this –

“The structures that allow for survival are bound to be temporary. Evolution is what happens when patterns that used to define survival become deadly.”

This is quite a wake-up call. She goes on to suggest that a helpful, if somewhat daunting, exercise is to take a mental trip through the unraveling and breakdown of a system or situation, going to the other side of what is feared and then asking how we would get along. Traveling back to the present from that point, what wisdom might we incorporate that breaks our current patterns? How might that help us to loosen our grip on what we know does not work, will not work and/or is ultimately harmful? Of course, the stakes (real and perceived) will be different for different people and contexts, but it strikes me as a crucial strategic question in this day and age to ask, “What can or must we let go of for the sake of life, liveliness and response-ability? If we don’t let go, then what?” Sometimes we do have to let go to see possibilities and our strengths. And it is also important to remember that there are tools and practices that can help people navigate the seeming void. More on that in a future post . , ,

“[We] cannot discover new oceans unless [we] have the courage to lose sight of the shore.”

-Andre Paul Guillaume Gide

Photo by Zach Dischner, shared under the provisions of Creative Commons Attribution license 2.0.

3 Comments

I love this post! It reminds me of a recent supervision session where I recognized (with help) that being always responsible leads to tightening of mind and body and less creativity. The rigidity trap. I am interested in the exercise of walking down the road and then retracing our steps to learn from the future (or maybe open our eyes to more of the present). Like most forms of fear, there is probably 20% reality and 80% imaginings.

Curtis, thank you! This is exciting stuff. And I’d add: the role of imaginary work (in particular dystopian novels) in these times is particularly powerful for daily micro-reminders of all this. When such work can be taken seriously, studied, and unpacked in the ways you describe, it provides a perfect and easily-accessible opportunity to “take a mental trip through the unraveling and breakdown of a system or situation, going to the other side of what is feared and then asking how we would get along. Traveling back to the present from that point, what wisdom might we incorporate that breaks our current patterns? How might that help us to loosen our grip on what we know does not work, will not work and/or is ultimately harmful?” Paolo Bacigalupi’s novel The Water Knife is one excellent example for our current stew of climate change, corporate rule, state’s rights, journalistic integrity, and the collapse of the nation…but really, it’s actually a fun read. 🙂

Anyway, thanks for this.

Anna

Thanks, Anna. It is exciting, if perhaps at least a wee bit daunting. More and more the necessity of letting go is coming up in the work I do (personally and professionally). And that imaginary work is crucial to avoid staring into the void, or retreating back to what we know does not work but is familiar. I can’t wait to check out The Water Knife. And I take heart in these words from Agnes de Mille – “Living is a form of not being sure not knowing what’s next or how. The moment you know ho, you begin to die a little.”

Cheers!

Curtis