Going Slow and Going Farther: Collective Impact and Building Networks for System Change

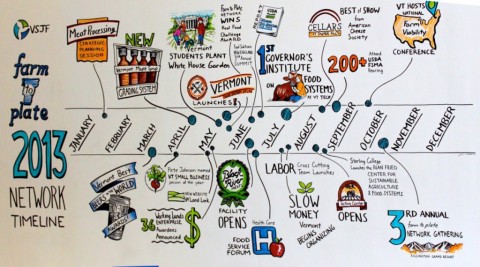

October 6, 2015 4 CommentsA recent report out of the University of Michigan and Michigan State University highlights a number of food systems change efforts that have adopted a collective impact approach. Two of these are initiatives that IISC supports – Food Solutions New England and Vermont Farm to Plate Network. The report distills common and helpful lessons across eight state-wide and regional efforts. Here I want to summarize and elaborate on some of the article’s core points, which I believe have applicability to virtually all collaborative networks for social change.

First off, the authors note the importance of context. They quote Margaret Adamek from the Minnesota Food Charter, who points out that “borrowing from other states and initiatives only goes so far as ‘the unique features of each place are what dictate the strategy.'” At IISC, we could not agree more. Complex systems suggest that we cannot bring a cookie cutter approach to change. As such, there is not one single appropriate model for food systems change. That said, the authors discuss common practices that can undergird a diversity of approaches.

- Investing time – It always takes longer than you think or want. While this may not be the best marketing pitch for collective impact and network building, it is good to manage people’s expectations. This work is a marathon, not a sprint. Undoing and shifting years of practices, layers of institutional structures and fixed mindsets does not happen over-night. Furthermore, it takes time to build alignment among key players.

- Building trust – A recent blog post in the Stanford Social Innovations Review says it all – “In our research and experience, the single most important factor behind all successful collaborations is trust-based relationships among participants. Many collaborative efforts ultimately fail to reach their full potential because they lack a strong relational foundation.” Trust is what binds the efforts together and creates longer-term and more emergent potential.

Change begins and ends with relationships, and a big part of systems change is rewiring and bringing greater depth (trust) to existing patterns of relationships.

- Being strategic about communication – Communication really is the lifeblood of networks. It’s what contributes to transparency, trust, social learning and adaptive capacity. Communication is not simply about one-way or one-to-many channels. Having myriad ways for people to connect and find one another helps to deliver value to more people in more ways.

- Using stories as strategy and evaluation – In complex systems, stories become an avenue for sense-making as well as a means of capturing diverse human experiences in a system. Stories can also provide qualitative data about how systems are changing, and they tend to have stickiness and staying power that can keep people motivated and coming back.

Powerful stories are like enriched compost that can be fed back into the network to nurture new growth.

- Tracking economic impact and other metrics – Arguably, economics underlies every kind of social change needed in this country. What I mean by this is that access to/ownership of resources of various kinds is key to power and self-determination, and affecting every system is the concentration and consolidation of power in ever fewer elite hands. Without tracking whether resources are growing in local communities and flowing and owned in more equitable ways, it is hard to say that we are making truly systemic change.

- Engaging diverse stakeholders – Another underlying factor in every systemic issue in this country is the growing crisis of democracy. From small towns to big cities, the composition of the public is becoming increasingly complex. At IISC, we see all of our work as striving in some way, shape or form to answer the question: “How can we build the will and develop the skill of the diverse public to collectively create just and sustainable societies?” We see a future in which we are “all in;” all in providing the information and knowledge needed to understand the issues that affect us; all in making decisions that impact us; all in, and especially those who are most often left out and are most negatively impacted. This push for more inclusive processes and structures is what we call Big Democracy. In this sense, engaging diverse stakeholders is not simply a means but an end in and of itself.

4 Comments